How I Learned to Stop Artspeak and Love the Editorial Process

Fortunately, there are dedicated editors with experience coaching artists to write compelling pieces that are intended to get results.

Provocateur art critic Jerry Saltz recently tweeted, “Artists complain about writing Artist Statements. You big babies; Man-up/woman-up. Just write why your work isn’t idiotic or just flowers or triangles or diagrams & say why it might be connected to archaic magic, consciousness trying to reveal itself, pleasure, or being useful.” Several days later, he tweeted, “For me there is no such thing as writing. There is only rewriting. I can’t write if writing is without editors. They save souls.”

Saltz makes a salient point in both tweets. Writing and editing are essential skills that bolster our ability to communicate effectively and convincingly. With the contemporary art world being bigger and more competitive than ever before, the strength of an artist’s writing can advantageously shape their career path. Good writing opens doors to many opportunities, including exhibitions, grants, residencies, and fellowships.

Writing is not an innate skill, and for many of us it takes significant focus and discipline before we become efficient at it. I can attest to this and so can all of my colleagues in visual art and art history circles.

I have spoken with artists who struggle to describe their work in a manner that can be understood by diverse audiences. They want to eloquently explain their work on a public-facing platform without alienating their audience by sounding too abstract or long winded. Oftentimes, their writing reflects how they speak to other artists but does not take the outside world into account. They fall into a habit of using “artspeak,” a form of grandiose prose that risks appearing pretentious.

When used as a formula for writing, artspeak can become vague and esoteric and provide very little meaning to anyone apart from the artist.

Unfortunately, good writing, although a key component for success in all undergraduate and graduate programs, is not universally taught throughout the BFA/MFA curriculum. Therefore, if we truly want to stand out from the field, it is up to us to take matters into our own hands and stop using artspeak.

Fortunately, there are dedicated editors with experience coaching artists to write compelling pieces that are intended to get results. Working with an editor is a good way to become a better writer in a much more tangible and goal-oriented timeframe. An editor will help you organize your grand ideas and concepts into texts that represent you, your work, and your career. Key documents that will benefit from collaborating with an editor include artist statements, biographies, press releases, CVs, and grant proposals.

As a curator, I value receiving hard copies of publications, such as artist monographs and exhibition catalogues. These texts, when done well, can make a lasting impression. Editors provide support and guidance throughout the publication process, from pitching a book to a publisher, crafting engaging copy, and ensuring that all materials are proofed, formatted, and ready for printing.

Overall, working with an editor is a great way to develop organizational and literary skills to incorporate essential artistic vocabulary and philosophical concepts into your writing an accessible and effective manner. Like Saltz, I rely on editors to provide feedback and guidance, ensuring that my writing comes across as understandable and meaningful.

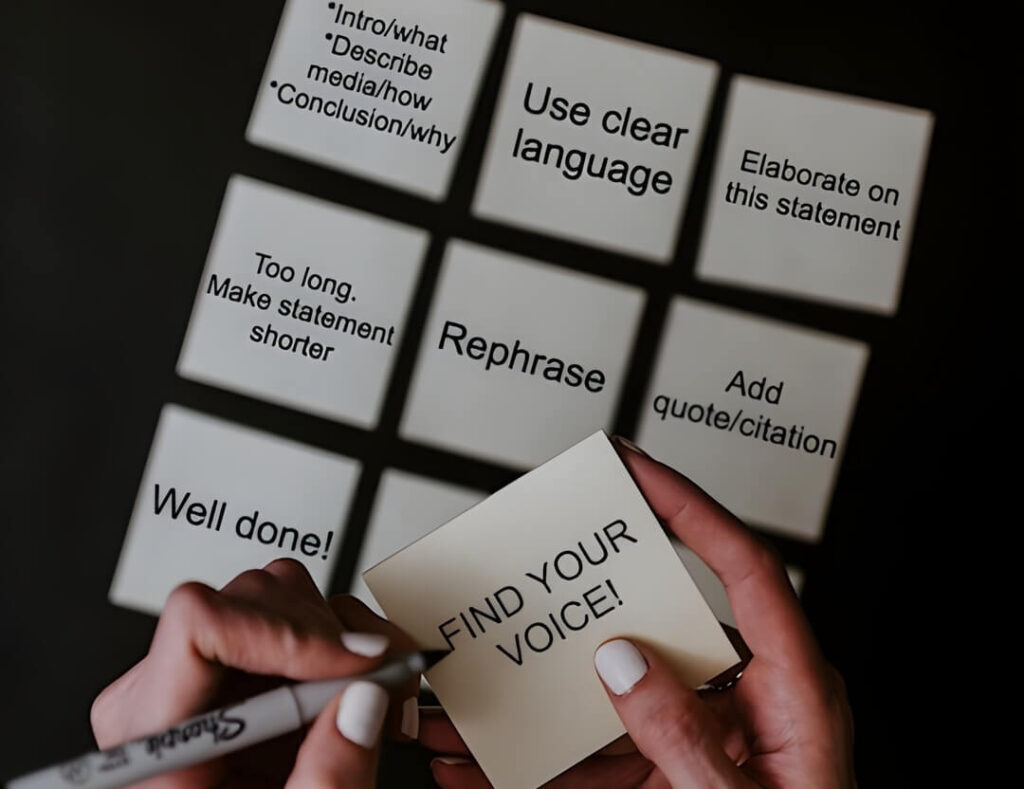

My aha moment came during graduate school, while I was writing a piece about an underrepresented contemporary artist. In my description of the work and its historical relationship, I filled pages with the typical art jargon of “isms” and other clichés. The artist reviewed the draft and made lots of comments in red ink, correcting my grammar, syntax, and historical context. His largest and most profound suggestion came as a shout: “FIND YOUR VOICE!”

In the absence of his editorial eye, I would have gone on to write generic and data-driven pieces, without expressing judgement and arguing a thesis. His prompt enabled me to rewrite the essay, taking a strong stand on why his work is significant and how it has impacted the art world.

He called me after receiving my revision in the mail, and it was the first time that I heard the ninety-one-year-old raise his voice in such a youthful manner, proclaiming “Well done!”

I recently found out that the artist’s brother consistently reviewed and edited his writing. I guess everyone needs an editor.

Get a rate quote or schedule a consultation call by clicking below.