Catalogues for art exhibitions, from the biggest blockbusters to the simplest single-artist debuts, are essential supplements to the show itself. As the art critic Sylvan Barnet advised in A Short Guide to Writing About Art, each catalogue entry should “help the reader to meet the work more clearly, more fully.”

So when approaching art exhibition catalogue editing, bear in mind that a catalogue assumes, in a sense, two roles. The first is factual: recording the presence of an artwork or object within an exhibition and providing the essential biographical data pertaining to it. But the second aim, just as important, is interpretative, carried out through critical essays and supplementary material such as bibliographies or artist statements.

Putting Together a Catalogue Presents Unique Challenges

For those compiling an art exhibition catalogue—usually a curator but sometimes the artist themselves—a daunting list of challenges await. Material is typically contributed by a pool of different writers, whether scholars, collectors, art practitioners, or other curators. These submissions from multiple authors will vary in language, approach, and tone of voice. They may even have undergone translation, adding another level of complexity to the edit. Artworks from different collections with different inventory standards may also be included.

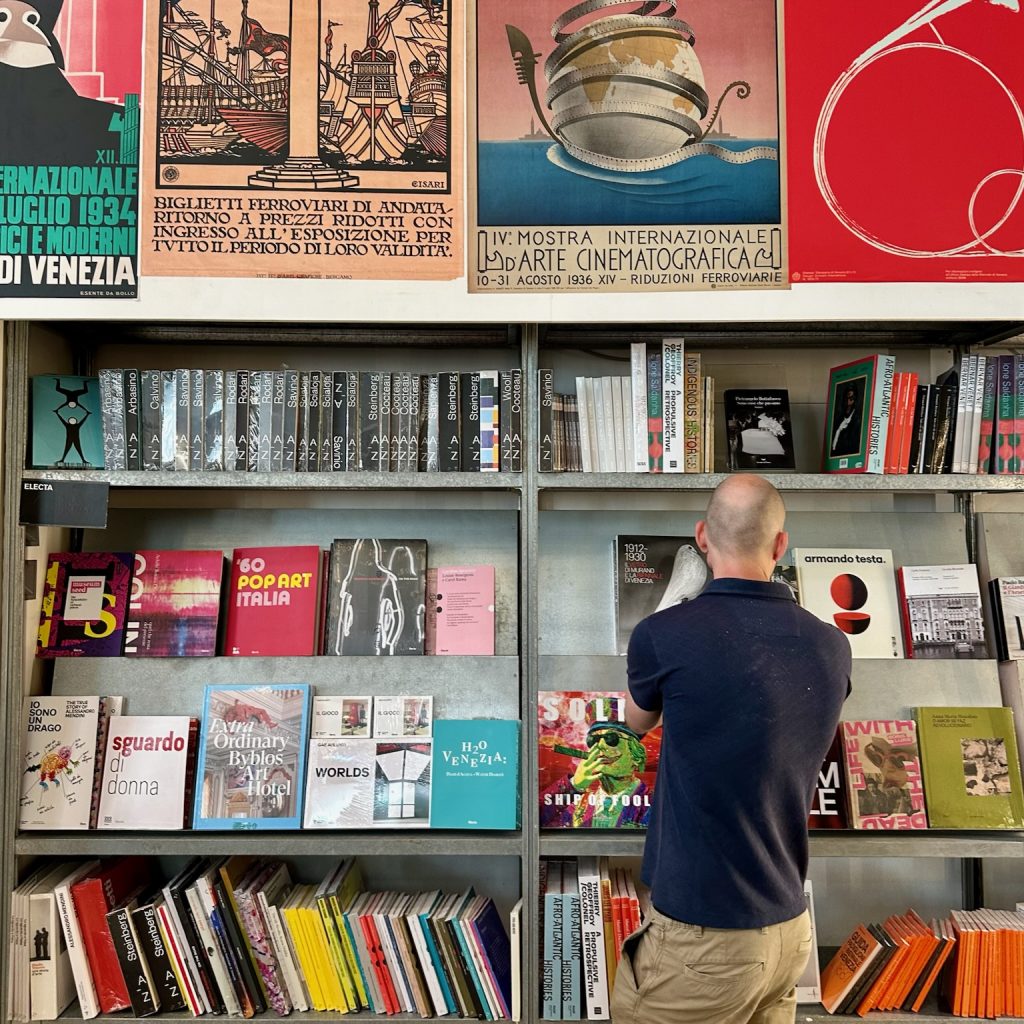

Such diversity can quickly lead to quite a headache, highlighting the need for competent editorial support to impose unity and consistency on the catalogue as a whole. When Flatpage edited Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere, the exhibition catalogue for La Biennale di Venezia 2024, we compiled and edited a collection of over 300 separate catalogue entries by nearly as many authors, many of which had to be translated.

So here are four tips for maintaining consistency and clarity in your next exhibition catalogue:

Know Your Audience

First things first, know your audience. The audience is the public who attends museums, galleries, art fairs, and festivals—a broad cross section of society. The language used in the exhibition catalogue must reflect this, imparting the latest scholarship in a language that is accessible and clear to all.

Yes, art historians would recognize a maquette, but make sure a maquette is defined in the text as a small-scale preliminary model so that it’s clear for all readers. And if only a specialist would get a reference to kilim techniques, for instance, how can the average museum visitor be expected to understand? (A kilim, by the way, is a handwoven reversible rug originating from modern-day Türkiye and Afghanistan—both these above examples popped up in Stranieri Ovunque.)

Art-historical jargon should be kept to a minimum and technical terms employed only when necessary. When they are used, define them so that they can be understood by the general reader.

Don’t Wait to Start a Museum Style Guide

Keeping your audience in mind, create a style guide and set the tone of voice. Early in the planning stage, put in place the initial guidelines to be used throughout every section of the catalogue. Designing a style guide can be an essential art copyediting service for museums, as there are a multitude of editorial decisions to be considered.

Begin with common editorial basics—the rules for punctuation and spelling, the styling specifics of citation formatting—but also take the time to envision any elements particular to the exhibition concept. Will the show include contributions by foreign artists, for example, whose works may have titles in languages other than that of the main text? Decide now whether such titles should be replaced by an English title (more accessible) or if the foreign-language title will be included with an English translation (which will add to the word count).

Good academic practice recommends the parenthetical inclusion of biographical information at the first mention of an artist, architect, or designer in a text. At the very least, dates of birth and death should be stated—but what about locations? And should nationality be mentioned?

Regarding tone of voice, will creators be referred to by their full name, their surnames, or even their first names? (It is still all too common for writers to use the respectful surname for male artists and slip into the familiar first name when referring to women.) And if the exhibition incorporates the work of living artists, do they favor the use of a preferred pronoun?

Make sure that this museum style guide is available to every contributor to the catalogue—ideally before they start writing! Having the guide available in a cloud storage service such as Dropbox, Microsoft OneDrive, or Google Drive ensures the latest updated copy is available to all.

Design a Catalogue Entry

The publication or museum style guide is also the place to lay out a template for a catalogue entry. An entry should give both the historical data and a concise scholarly analysis.

It is typical to head each entry with the biographical components of the artwork (the who, what, when, and where, also referred to as the tombstone. Scroll below for more about this). This is usually followed by a passage of interpretative text specific to the artwork—it may discuss the subject matter and its meaning, or the inherent value of the work. It could explore the artwork’s relevance to the artist’s development or the exhibition theme.

All in all, an effective entry should develop the reader’s appreciation, encouraging them to revisit the work on display for a deeper understanding. Catalogue entries may vary greatly in length, but if space is at a premium, it is wise to impose a word limit. Each entry for the Venice Biennale catalogue was limited to 300 words, including the tombstone.

Know Your Tombstone Data

The tombstone component of a catalogue entry reflects the life of the artwork or object and may include different elements depending on the subject matter, the exhibition theme, or just available space. A comprehensive tombstone could include:

· The artist’s name (followed by nationality and lifespan dates)

· The title and date of the artwork

· The medium and dimensions of the artwork

· Defining features such as signatures

· The artwork’s provenance

The tombstone template for Stranieri Ovunque was pared back yet precise, as can be seen here:

Clorindo Testa

Benevento, Italy, 1923–2013, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Pintura o Círculo negro, 1963

Oil on canvas

150 × 150 cm

Collection of Eduardo F. Constantini

Each of the components of the tombstone demands certain styling decisions. Take the two numeral elements: dates and dimensions. How will the lifespan dates be styled—1920–1999 or 1920–99? Are there dates that go back far enough to use era abbreviations, and if so, will BCE and CE, or BC and AD be used? What term will be applied to convey time-period uncertainty—approx., c., ca., or circa?

And what about dimensions? The norm is to list the height of an artwork before the width, such as 55.2 × 45.5 cm. But will the metric (cm) or imperial (in) system be used? Or, indeed, will both appear? Have you used the multiplication symbol correctly? (The × in the previous example isn’t the letter x!) How will fractions be displayed if using the imperial system—as separate characters (1/2) or as a single character (½)?

Having a clear template early on will help reduce the need for editorial corrections at later stages of the process.

Conclusion

Know your audience; know your voice. Consider the editorial guidelines for the structure of the catalogue and make them accessible to all contributing parties. A little preparation and forethought can lay a solid foundation for a clear and consistent exhibition catalogue.

FAQ

What should be included in a catalogue entry?

How do you create a style guide for an exhibition catalogue?

What is tombstone data in museum publishing?

Why is consistency important in catalogue editing?

Contact the team at Flatpage by clicking below. Book a free editorial consultation and get 10% off your first service!